There’s something special about the number three. The rule of thirds. The Holy Trinity. The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.

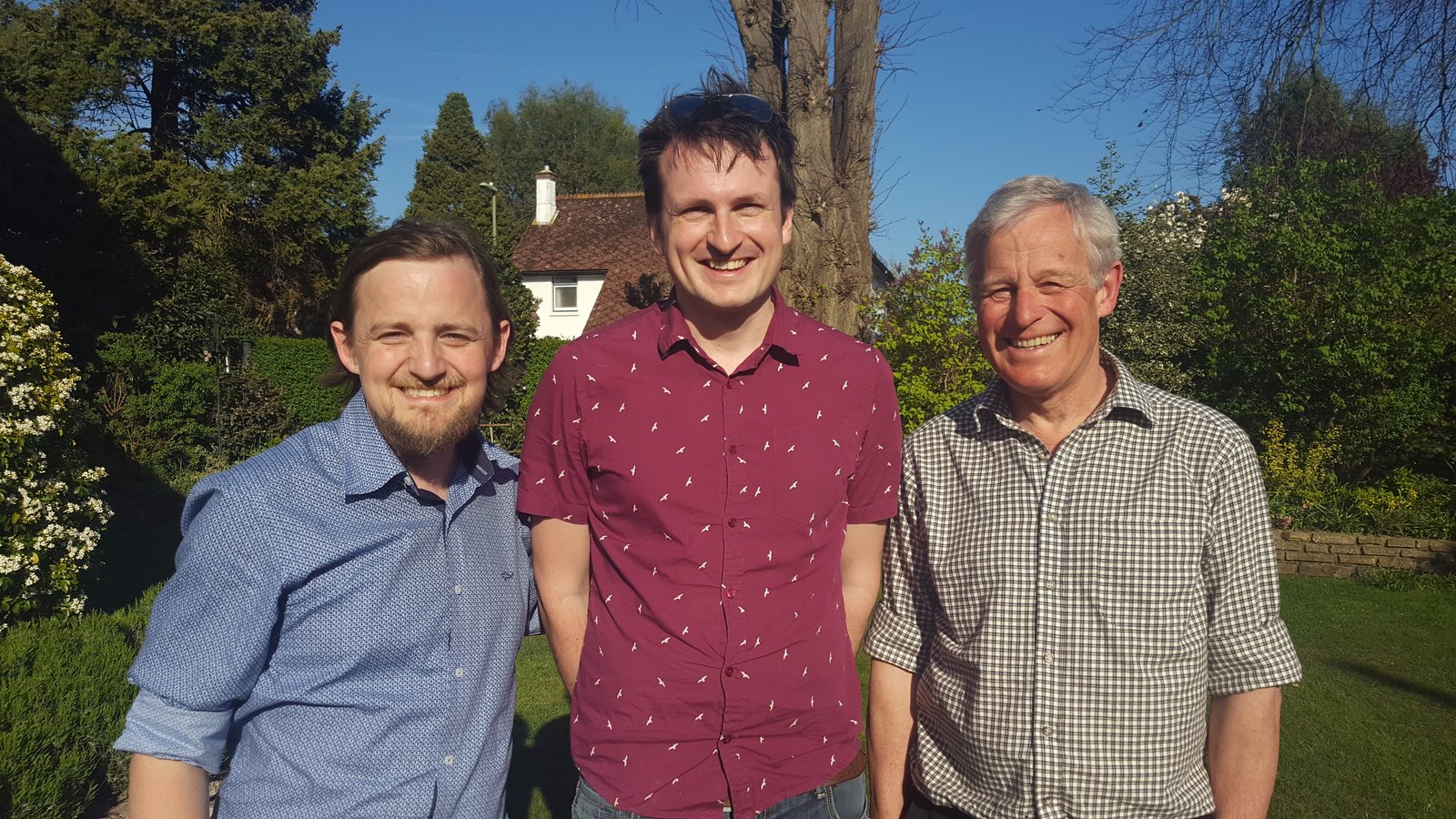

Earlier this year I turned three. Three years ago, my new birth day (Day Zero, the day of my transplant) had a lot riding on it, to say the least. My first birthday was a huge milestone, not least because it meant moving from counting months to counting years. The second anniversary marked the potential – then realised – end of anonymity between me and my donor, who turned out to be a thoroughly decent chap called Tim.

Turning three boasted nothing quite so epic – but in many ways that was what made it so special. It was the first commemoration of my lifesaving transplant not to carry the weight of another tick in the box, another item to be crossed off my ‘to achieve’ list, accompanied by a sigh of relief. It was simply and purely a celebration of life.

Three cheers

So many great things have happened since my transplant, but when it comes down to it, they’ve all been side-effects of the ‘bonus’ life my donor’s stem cells gave me. Most milestones, though, brought the precariousness of my existence into sharp focus. Most of the reasons donors and recipients have to remain anonymous for two years after transplant in the UK relate to the fact that those first two years are the most risky.

I’d never take surviving another year for granted, but whereas I had eagerly (and slightly nervously) anticipated my first and second birthdays, my third just happened. And when life is just happening, three years after a generous medical marvel, the fog clears and you can start to appreciate how special it is to be alive. It’s like seeing something beautiful you’ve already ticked off in your i-SPY book: now you can appreciate it fully just for what it is.

The other one

I’m the third child of four, too. I always delight in complaining that while my elder brother got to be the eldest, with all its trailblazing connotations and attentive parenting; my sister was blessed to be the only girl, with the unique privileges and natural defiance that brought; and my younger brother gathered the spoils of being the youngest (a Gameboy, for a start!), I was left to be ‘the other one’. The third child, but not the youngest. The middle child, but skewed off-centre by virtue of not being the sole occupant of the role.

But maybe that role – or lack of one – gave me a freedom from the expectations weighing on my siblings. The achievements of the first two before me were impressive, but diverse enough to leave my own road open (or closed, if I preferred: I learnt to drive far later in life than any of the others). The milestones in my life marked off the years, but didn’t demand any greater meaning than celebrating another 365 days of life.

Bronze benefits

Even in the sports arena, coming third brings its own surprise benefits. Win and the pressure’s on to set a champion’s example, defend your title and respond to all the media demands. A silver medal, though, reminds you how close you were to reaching the pinnacle, and makes you feel you need to push yourself even harder to reach it. Someone once advised me to avoid coming fourth: it’s agonising to miss out on the three medals – to be in a sense the first loser.

But a bronze medal? You’ve achieved something, but you weren’t so close to winning that you wish you’d trained just that little bit harder – you had two opponents to overhaul, after all.

Reaching three years post-transplant was great, just for being what it was. I’m more than happy with that.